Some say City Hall’s scheme to improve public transport with a bus line is failing. One architect has a new plan, tried and tested throughout the developing world.

With the capital growing and incomes on the rise, rush hour in Phnom Penh is only getting worse as more and more motorbikes and tuk-tuks compete with sedans and SUVs for ever-dwindling space on the asphalt.

While a limited public bus service was introduced in the capital earlier this year, and new routes are planned, Prime Minister Hun Sen last month declared early efforts a “failure”.

One architect believes that the city’s best bet is an alternative and time-tested bus system that has taken off across the developing world from Bogota to Jakarta.

Ruben Castillero-Mortera, an architecture professor at Raffles International College, has drawn up plans for a “bus rapid transit” (BRT) system that calls for more than 100 stops around the city along seven lines.

But the buses wouldn’t have to grind through traffic to reach their destinations – two lanes in the centre of the city’s main roads would be reserved exclusively for the buses.

Castillero said that the concept was far more cost efficient than subways, an idea floated earlier this year by private investors and the city municipality.

“I think this can open [Cambodia] to the world, to start thinking about something more realistic than a metro or monorail,” the 39-year-old Mexico City native said last week.

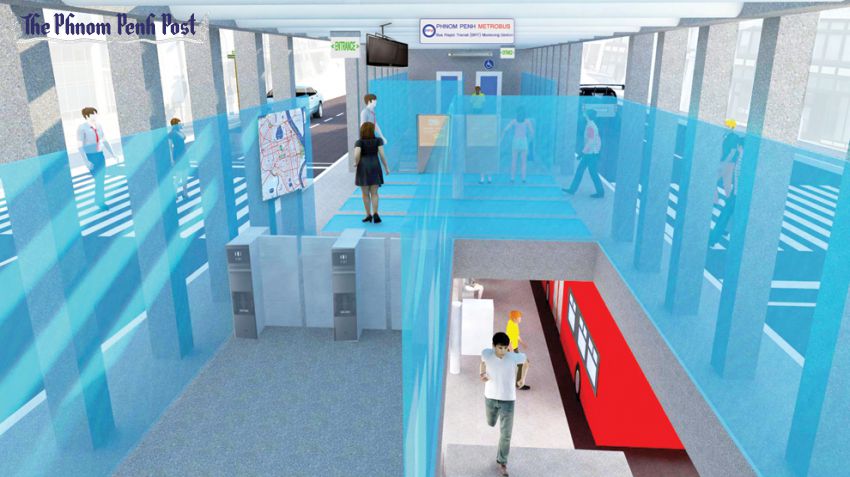

Castillero’s design calls for passengers to use automated ticket machines to access platforms from which they would board the buses.

The stations would be underground to minimise obstruction to regular street traffic, although the bus lanes between stations would be at street level.

The system’s dedicated bus lanes would allow for a network that functions with the efficiency of a subway, he said, without the tunnels, railways or trains. Although the cost of a BRT would run into the millions, it would be far cheaper than building a subway.

Although the system would reduce road space available for other vehicles, Castillero said that an efficient BRT would reduce the city’s overall traffic. “At the beginning, some motorists will complain that they have less space to drive, but having a rapid transit system running would be beneficial for all,” he said.

Castillero has yet to pitch his plan to City Hall, but it will be formally unveiled at the Our City 2015 festival. If the municipality accepts the design, it would be the largest project ever carried out by the architect, who worked freelance in both Mexico and the UK before becoming a professor.

“I kind of formed it for my pleasure to participate in the Our City festival more than as a proposal. But then I started to develop research and reached an outcome,” said Castillero, who holds a master’s degree in Advanced Architectural Studies from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow.

About 180 cities currently have a BRT system, with Latin America holding the largest share.

Among the most successful is Bogota’s BRT system in Colombia, which prompted the US Department of Transportation to state in a 2006 report that the city’s system provided “irrefutable evidence of what BRT can do”.

But City Hall spokesman Long Dimanche said Phnom Penh needs to develop a functioning conventional bus system first. He said: “Next month, we will have three bus lines, so I think it will work very well to serve the people in the city.”

The BRT concept has made some inroads in Southeast Asia. At about 200 kilometres in length, TransJakarta’s BRT is the largest in the world. Bangkok’s BRT has a single route and covers 16 kilometres.

But while many systems use complicated networks of underground stations, Dinesh Mohan, a professor of biomechanics and epidemiology at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi who has conducted extensive research in Indian BRT systems, said a BRT could be as simple as having a single slice of road reserved for public transport.

“BRT means very different things to different people. The main issue is [to have] a very well-integrated public transport system [and] for lanes to be reserved for public transport,” Mohan said in a phone interview from New Delhi, adding that his city ought to expand its miniscule BRT network.

Whatever the details, the city’s rapid development puts greater urgency to develop a feasible mass transit system, said Castillero.

“It is ideal to start planning for the future a proper sustainable transport system like a BRT, [rather] than trying to minimise the traffic, with human-hours wasted with minor solutions and delaying the problem even more while the mobility of the city collapses.”

Source: Phnom Penh Post